The IPO Frenzy Amid Economic Turmoil

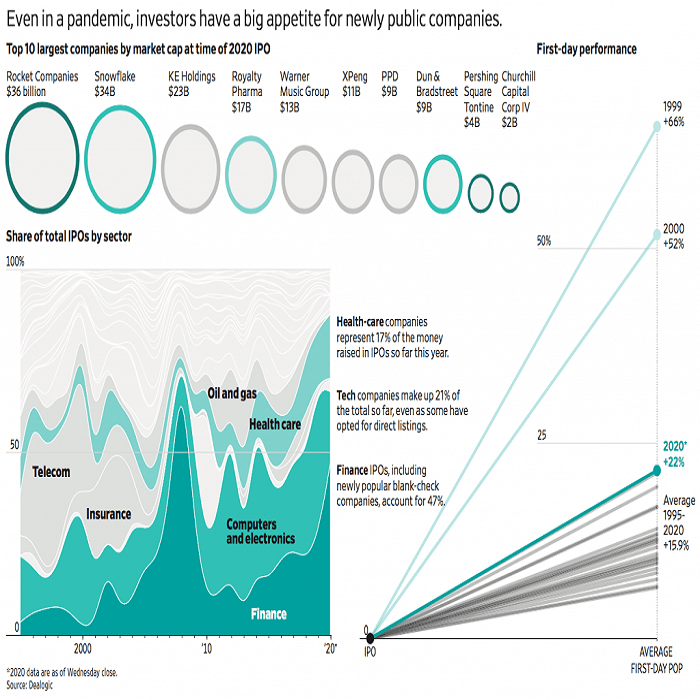

In the midst of a recession, the U.S. IPO market has become oddly heated—so much so that it’s drawing comparisons to the infamous dot-com bubble. While many businesses are struggling and millions of Americans have lost their jobs, IPOs are booming and experiencing one of their busiest periods in years. By all measures, 2020 could end up being the largest year for IPOs in recent history.

With three months left in the year, U.S. companies have already raised $95 billion through IPOs—surpassing every year since the dot-com bubble burst in 2000, with the exception of 2014 when Alibaba’s listing alone made up over a quarter of the total $96 billion.

Bankers, lawyers, and executives now believe that if this pace continues, the 2020 IPO market may even eclipse the frenzy of 2000, when investors frantically poured money into internet stocks.

A Disconnect Between Markets and the Economy

The current IPO boom is unfolding alongside an economy still reeling from COVID-19. Massive business closures and record unemployment in spring 2020 highlighted deep economic distress. Yet, the pandemic has also reshaped the economy—accelerating the shift toward digital services in work, education, and communication, thereby inflating the valuations of companies providing such solutions.

Moreover, with interest rates at historic lows and traditional investments like bonds offering minimal returns, investors are searching for more lucrative opportunities.

This year, more than 80% of IPO capital has flowed into just three sectors: healthcare, technology, and blank-check companies (SPACs). Not since 2007 has the IPO market been so concentrated. That year, right before the financial crisis, saw a flood of banks and lenders going public.

A Record Year for Listings

Over 235 companies went public in 2020—more than in any year since 2000, when 439 firms debuted. Major companies like Airbnb and Palantir Technologies are also expected to join the market before year-end.

Even Warren Buffett, traditionally skeptical of startups, entered the IPO scene. His company, Berkshire Hathaway, invested $735 million in the IPO of data warehousing firm Snowflake. On its first trading day, Snowflake’s shares more than doubled, closing above $250 and making it the year’s biggest tech IPO. The company’s market value hit $70.4 billion, and Berkshire’s stake appreciated to $1.6 billion.

The IPO Market’s Revival

This marks a sharp contrast to recent years, when many declared the IPO market dead. For over a decade, firms preferred raising capital privately—SoftBank’s $100 billion Vision Fund being a prime example. Staying private allowed startups to sidestep regulatory disclosures and public shareholder scrutiny. In 2016, IPOs raised less than $25 billion.

Now, firms fear staying private too long. Companies like Uber and Lyft, which went public under less-than-ideal conditions in 2019, serve as cautionary tales. Today’s startups aim to go public while still growing, rather than waiting until growth slows.

Alternative Paths to the Public Market

For decades, the IPO process followed a rigid formula. But in recent years, alternatives have emerged. One such path is through blank-check companies or SPACs (Special Purpose Acquisition Companies), which now account for over 40% of IPO fundraising—compared to a 10-year average of just 9%.

Eventbrite co-founder Kevin Hartz launched his own SPAC this year. His initial meeting with bankers was in early January, and within 60 days, his company had gone public—raising $200 million. He was surprised at how quickly the process unfolded, and believes SPACs have a promising future.

Another alternative is the direct listing, where companies register existing shares held by employees and investors for public trading—allowing liquidity without raising new capital or paying hefty underwriter fees. Palantir, co-founded by Peter Thiel, is set to go public via direct listing with a valuation of $22 billion.

In late August, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission approved a proposal to allow companies to raise capital via direct listings—though recent investor backlash may delay its implementation. If enacted, this reform could solve direct listing’s biggest flaw and make it more mainstream.

COVID-19 and the IPO Process

The pandemic has also transformed the IPO roadshow. What used to be 8-10 day international tours to court investors are now brief, virtual meetings—ironically increasing investor participation.

How COVID-19 Reshaped Public Markets

The COVID-19 crisis triggered shutdowns, limiting access to private capital. Startups were often forced to settle for lower valuations or raise smaller rounds. Meanwhile, the public markets froze in March—until the Federal Reserve intervened by purchasing bonds and injecting liquidity. As S&P 500 rebounded, bankers rushed to launch IPOs that had been shelved.

To ensure successful offerings, underwriters coordinated closely with major institutional investors like Fidelity and T. Rowe Price to pre-allocate large share blocks.

The boom in SPACs this spring also signals that investor demand for IPOs exceeds the number of companies ready to go public. While SPACs have existed for decades, they gained legitimacy in 2020 after high-profile firms like Virgin Galactic and DraftKings went public via reverse mergers with SPACs.

منبع:

“The IPO Market Parties Like It’s 1999”,Wall Street Journal, 26 – ۲۷ September 2020

—–

bonds (۱

blank-check companies (۲

data warehouse (۳

regulatory disclosures (۴

No comment